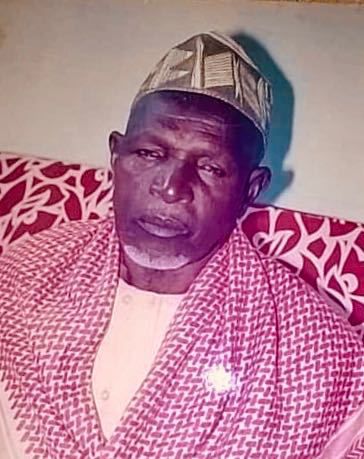

Today I wish to share the story of my grandfather. Although he died when I was just 10 years old, he remains my greatest inspiration. Allassani was his name and he was born in Kabou, a small town of North-Western Togo predominantly inhabited by Bassari people. His father established himself there along with other Anonfo people who are actually based in the northern town of Mango. They were sent as warriors to support the Kabou king fight the Kokomba warriors who raided the village occasionally to steal their crops.

The Tchokossi themselves (alternate name for the Anonfo) were in the village raiding business. They along with the Konkonba and Tem people were the only warriors of northern Togo. While the Tem lived mostly of slave trading, the Konkonba and the Tchokossi lived of raiding peasants in the north. The Tchokossi who are predominately Muslim usually offer a deal to the communities they raided. They could convert to Islam and obtain their protection or reject their conversion and face tribulations. The people of Kabou not having much choice between them and the Konkonba agreed to obtain their protection and convert to Islam. Tchokossi warriors were deployed to Kabou to protect the community along with religious clerics who were to ensure its islamization. My great grandfather was one of them.

I wish not to waste too much time on my grandfather’s origins but it is important to note that their ethnic group resisted French colonialism along with the Konkonba mostly because they didn’t want to lose control of the villages they had conquered. The Konkonba paid the biggest price with over 3000 of their warriors killed. The Tchokossi king Nabiema Bonsafo also lost his life in the war against the French troops. That rejection of the French domination is also enforced by their Islamic background which makes them see white missionaries as enemies and the little control they had over peasant communities were now under French rule. As an act of resistance, the Tchokossi refused to pay their taxes (collected as crops) to the French administration by choosing not to farm. They never had to farm before the French arrived anyway. The Germans left them alone for the short time they were there but the French were more coercive by attempting to assimilate them.

My grandfather and his brother were arrested one morning of 1948 for refusing to pay taxes to the French administration and they were taken to the King’s court. The King of Kabou who benefited from the support of the French administration and became loyal to them decided to tie them to a tree inside his compound as punishment. A teacher of the Guin (Mina) ethnic group who was deployed to teach at the elementary school of the village was outraged by the news of two men tied to a three for refusing to pay taxes. The man intervened for their release and considering that teachers were highly respected back then, the king set them free.

My grandfather then visited the teacher at his house to thank him. The teacher told him the only way he could thank him is by sending his children to school. My grandfather hesitated because he didn’t believe in western education and he told M. Mensah he couldn’t allow his children to spoil and become as selfish and wicked as the White man. M. Mensah convinced him by telling him he himself attended the White man’s school but isn’t wicked and selfish; he wouldn’t have stood up for him if it was the case. Then he went on to explain to him what colonialism is and told him that education is important to fight it and his children will not undergo the same humiliation if they were educated. My grandfather therefore decided to enroll one of his sons. The very son who was of no use to him because he was often ill as he didn’t think he had much to lose by sending that son of his anyway. That son was my father. My father was the very first of his siblings to enroll in school and he had to deliver daily reports of what he was learning in the White man’s school because my grandfather was curious to know what his son was being “brainwashed” with.

Few months after my father enrolled in school, M. Mensah, the teacher who convinced my grandfather to register him suffered a stroke. His family then came to Kabou to repatriate him to his village in Southern Togo. My grandfather followed his new friend and spent about six months carrying for him till M. Mensah passed away. While caring for M. Mensah, my grandfather was introduced to the struggle against colonialism led by Sylvanus Olympio. He decided to join the CUT, their political party although he couldn’t speak Mina which is the language mostly spoken in Aneho by the Guin ethnic group and in some other parts of southern Togo. He couldn’t understand much of what they were saying but his friend M. Mensah although paralyzed on the right side after his stroke served him as interpreter.

Following the death of M. Mensah, my grandfather returned to his village Kabou in northern Togo to share the news of the independence struggle which most northern communities were unaware of. My grandfather got arrested, stripped naked and beaten on market day by French soldiers for daring talk about independence. This outraged the members of the community who felt insulted by such barbaric act. Then more young men decided to join my grandfather in the struggle for independence. They held secret meetings and sent delegates to the CUT’s rallies in Aneho. When the French heard of such, they arrested them all, expelled their children from school and worse forbade them to seek health care in the dispensaries which the French consider as benefits of colonialism. They were also banned from using public transportation as the French didn’t want them to attend the CUT’s gatherings.

My grandmother paid the highest price during these years of resistance. She lost multiple babies as she was denied access to the dispensary to deliver them. My grandfather and my father were mostly affected by the death of my uncle SANI who was less than two years old when his twin brother Awali and him contracted measles. They were denied access to the dispensary and Sani died while my grandfather was in prison. My father said the day my grandfather returned from prison and found out his son had died was the only time he has ever seen him cry. “He was a broken man” said my father. His determination to end colonialism only grew stronger.

To raise money for the struggle, my grandfather, his brother and their comrades who once refused to farm decided to start farming. Not to pay their taxes to the French administration but to raise money to support the struggle. They would sell one third of the crops and send the money to Pa De Souza who was the treasurer of the CUT. To attend the CUT’s national rallies they would walk back and forth from their village to Aneho. It was taking them about three weeks to complete the round trip by feet because they were denied access to public transportation and were too poor to afford a vehicle. About few years into that, they were able to raise money to buy a bicycle and my granfather and his friend would bike from Kabou to Mango (their village of origin which is further norther) to rally with their people who also had a strong independence movement there. From Mango they would bike all the way to the South stopping by cities like Atakpame, another stronghold of the independence fighters. To feed, they hunted animals and will sell part of it to buy yam which they grilled to eat with their meat.

Eventually, the struggle paid off as they succeeded at collecting the signatures needed to petition the United Nations for Togo to obtain its independence. Togo which was placed under French mandate after Germany lost the world war could petition the United Nations over the human rights abuses of the French administrators and it took men like my grandfather to send these reports from all over the country to the independence struggle leaders. The collaboration between the educated elite and the uneducated mass was strong and this despite cultural, religious and linguistic differences. They all spoke the language of independence and were very loyal to their cause. My grandfather befriended comrades from all over the country and considered them brothers.

In 1958, on April 27 Togo held the very first independence referendum in French Africa and won it. The people voted for independence and the administration asked for two years to prepare their exit. On April 27th 1960, Togo became independent thanks to the sacrifices of thousands of Togolese men and women from all over the country. My dad recalls that one morning of 1963 my grandfather and my grandmother were discussing politics and my grandmother was insisting the French was behind it. My grandfather rather believed it was the work of the envious brother in law of Sylvanus Olympio , Nicolas Grunitzky who was made president after Olympio got killed on the 13th of January 1963. My father didn’t really understand the implications of the coup but he recalled my grandfather was angry. He said the French would walk over his dead body to reconquer Togo if they truly had a hand in the coup.

Few days later, my grandfather and his comrades were arrested by the military. His brother managed to flee the village to neighboring Ghana but got arrested there by Nkrumah forces because he was accused of mobilizing the people of “western Togoland” (now Eastern Ghana), which was placed under British mandate and chose to obtain its independence with the Gold Cost to form modern day Ghana. Indeed, there was a beef between Olympio and Nkrumah as the later believe Olympio wanted to reconquer British Togo and his supporters were seen as enemies of Ghana. My grandfather was in prison in Togo for organizing against the puppet government the French had installed and his brother was imprisoned in Ghana for organizing with secessionists. They both regained their freedoms when both governments didn’t consider them a threat anymore. But that didn’t affect their dedication to the struggle. For them, rather die than be subjugated.

In 1967, They managed to mobilize against the government of Nicolas Grunitzky, the French puppet brother in law of President Olympio who was despised by the majority of the Togolese people. A revolution was ongoing in the whole country as the independence leaders reorganized their bases to get rid of him. Eyadema Gnassingbé, one of the soldiers of the French colonial army who assassinated Olympio in 1963 carried a second coup and toppled Grunitzky on the 4th year anniversary of Olympio’s assassination when independence forces planned a demonstration which the French were scared would cause an uprising. An army official who was more educated than Eyadema was made president but his drinking problems didn’t allow him make use of such opportunity. He was toppled few months later again by Eyadema Gnassingbé on the 14th of April 1967 and he will rule Togo till he died in 2005.

The French instructed Eyadema to be tougher towards CUT’s members to avoid a repeat of the uprisings that shook Grunitizky’s government. The military regime of Eyadema was pitiless towards members of the CUT. The vast majority were either shot dead or tortured or starved to death. Those whose lives were spared after months of torture retained severe injuries. One of my grandfather’s friends lost his sight to torture. My grandfather left prison in 1967 weakened by months of torture and decided to focus on his farming and hunting as most of his comrades were either dead, disabled or in exile.

Few years later, my father now about to take the BAC exam (pre-college exam) was denied registration on the basis of bearing a foreign (Arabic name). Indeed, Eyadema had decided to copy the “politics of authenticity” of his dictator friend Mobutu of Zaire (current day Democratic Republic of Congo). All foreign names were banned and the most targeted groups were the Christians and the Muslims. Eyadema himself went from Etienne Eyadema to Gnassingbé Eyadema. The people of Togo were required to change their names to tribal ones or be expelled from school, fired from public service or denied of certain rights.

My grandfather told my father Eyadema is not his God and doesn’t get to choose his name or that of his children for him. My father who had no option as it was a requirement to register for the exam decided to make up his own last name. He combined Na (which means grandfather) to Bouraima (the name of his grandfather, my grandfather) into Na-Bouraima. He was told that spelling was too complicated at the registry service and was given Nabourema. My father then passed that name to his younger siblings who were also required to change their names at school.

After my father finished high school, he enrolled in philosophy at the University of Benin (now known as the University of Lome). He would embark on writing and distributing leaflets against Eyadema’s regime and got arrested. When my grandfather heard of my father’s first arrest, he had a letter written and sent to him telling him not to lose hope and not give up on the struggle. My father will spend the next few years between prison and the university until he got expelled for life in his final year for recidivism. A scholarship he obtained to pursue his graduate education in Switzerland was revoked along with his passport. Of the times my father was in prison, why grandfather would send crops to support my mother and assigned his youngest son Awali (the surviving twin) to come assist my mother care for the children while his brother was in prison. My uncle later died in 1991 of stomach cancer raising my grandmother’s children death toll to 10 as my father and his younger sister became her only surviving offspring.

My grandfather’s health deteriorated and he died on December 25 1999. Before passing away, he told my father that his only wish was to see the neocolonial regime of Eyadema fall so he could carry the news of their victory to our martyrs but he entrusts him with the struggle. Unfortunately, two generations later, the struggle continues and I hope my children will not inherit it. I have been accused of having a personal vendetta against this regime because they had tortured my father. While that is enough reason to stir my anger against them, the sacrifice of my grandparents and their generation is what keeps me going. I see my abdication as an act of treason against them because they gave their all to the struggle of our liberation. Without a formal education, money, electricity, telephones, a steady income, a vehicle, they fought for us and they stood against one of the toughest colonial powers on earth. I try to imagine the nights they spent in the bush while traveling to attend their party’s rallies, the children they lost as a result of them being denied healthcare, the torture they endured in prison just to name these few and that reminds me of how easy things have been made for me and my generation thanks to them not giving up on us even though they had every single reason to.

Today I can claim a Togolese citizenship because way before I was born, thousands of men and women joined their hands to make Togo a free nation. I may not carry my grandfather’s name to honor him, but I am proud to carry his courage and his patriotism. 60 years ago, in March 1958, they embarked on an independence campaign asking all the inhabitants of Togo to vote “No” to colonialism during the referendum. Today the people of Togo are being forced into another referendum but this time around, they are limited between choosing to endure Eyadema’s son for another decade or allow him rule Togo for life like his father. As my grandfather would have told the father I tell the son: OVER MY DEAD BODY!

FAURE MUST GO NOW!

Farida Bemba Nabourema

Disillusioned Togolese Citizen

![]()

/image%2F1017630%2F20210128%2Fob_dee76c_e6bb41e7-7788-4f5c-99db-071b0f262048-1.jpeg)